Hello,

After a few lovely warm and sunny days here, we’ve got a rather rainy Monday in progress today. It reminded me that I’ve half of “Words Weather Gave Us” written, including the chapter about rain words. So here, to hopefully cheer you up on this damp day, is an extract about puddles and their sinister cousins – beau traps.

Puddle & Beau Traps

{extract from “Words Weather Gave Us” copyright Grace Tierney 2024}

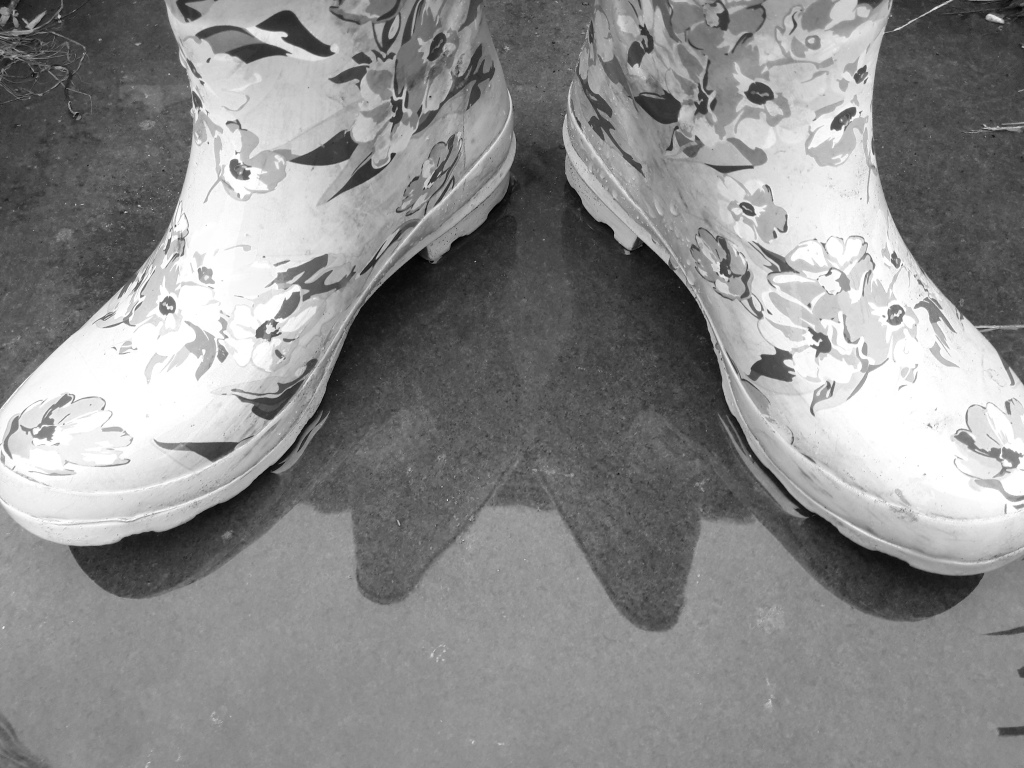

A puddle, which has been with us since the early 1300s, is defined as a small pool of dirty water. Puddle-jumping enthusiasts will point out that they’re also perfect entertainment locations for small children and life-loving adults, especially when approached with suitable footwear.

In line with the idea of making lemonade when faced with an excess of lemons, wet countries should adopt puddle-stomping as a national sport. Free, accessible to all, energetic. It could be the next big thing at the Olympics. Synchronised jumping for a team event perhaps?

The word came about as a diminutive of pudd (ditch) in Old English and is related to the charming German word pudeln (to splash in water). Originally puddle was used for pools and ponds as well which explains puddle-duck (a domesticated duck) which we’ve had since the 1800s. Beatrix Potter published her book “Jemima Puddle-Duck” in 1908.

The stealth version of the puddle is the beau trap. My home city, Dublin, has plenty of these. A beau trap is early 19th century slang for a paving stone which is loose enough for rainwater to gather underneath. Dublin city dwellers will know water gathers under some of the large Georgian stone footpaths (sidewalks for my US friends) and unless you avoid those slabs or hit them in the exact right spot it “tips up and pumps half a litre of rainwater up your trouser” (as Terry Pratchett points out in “A Slip of the Keyboard”). This rainwater is always a murky grey shade and invariably ice-cold.

Douglas Adams once created an alternative word for this, the affpuddle.

Why is it called a beau trap? The elegant young men of the 1800s (also known as beaus) wore those tight white stockings to show off their well turned ankles and calves. A sinister pool of city rainwater was a terrible trap for those beaus.

Until next time happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. Want more Wordfoolery? Subscribe to the monthly newsletter “Wordfoolery Whispers”. Sign up to avoid missing out! Don’t forget to click on the confirmation email, which might hide in your spam folder. There will be a new issue this week